What are Character Archetypes? A Definition.

"Model, first form, original pattern from which copies are made." - Oxford English Dictionary, 1600

"Pervasive idea or image from the collective unconscious." - Carl Jung

The term ‘archetype’ is based on the ancient Greek words ‘arche’ meaning ‘beginning, origin’ and ‘typos’ which means ‘pattern, model or type’. The combined meaning could be interpreted as ‘original model’.

A character archetype in novel terms is a type of character who represents a universal pattern, and therefore appeals to our human ‘collective unconscious’ .

For example, ‘hero’ is the most fundamental character archetype, which directly corresponds to us each being the hero (or protagonist) of our own life story.

The next most common character archetypes are: opponent, mentor and love interest.

It’s no coincidence that in our lives we all have people that make life difficult, people who help and guide us, and people who we fall in love with.

By skilfully applying the principles of character archetypes, writers are able to create well balanced casts of characters that emotionally engage readers by tapping into our fundamental nature.

Using Character Archetypes to Create Characters

Plato believed that all physical forms were derived from a single, original archetype.

For example, there is one original, utterly perfect bird, which has the qualities of being small enough to comfortably fit in your hand, having a straight, wedge shaped beak, having a beautiful singing voice, being able to fly and having feathers.

That original is the ‘archetype’. All other birds are deviations and variations on that.

Plato’s ideas might cause a few raised eyebrows in scientific circles these days, but they are extremely useful for making sense of the chaos of creativity.

The perfect hero

In the same way as the bird, we could propose that there is a ‘perfect’ hero. This hero has certain qualities, such as being principled, moral, brave, attractive, likeable, confident and good at fighting.

Most heroes in most stories will share those qualities. However, it is possible to deviate from the archetype and still have a beautiful bird (or hero).

So you might create your hero to be brave, moral and attractive, but completely useless at fighting. They don’t fit the standard stereotype, but as long as they have enough of the established qualities of a hero, they will still tap into our subconsciousness understanding of a hero.

After all, there are birds that don’t even fly, and what could be more fundamental to a bird’s identity than flying?

Of course the further you deviate from the original archetype, the fewer people will identify a character as being that type of character.

That isn’t to say that deviating is a bad thing – breaking the rules in itself can be incredibly powerful – but you can be far more effective if you know what the rules are and why you’re breaking them.

Commonly used Character Archetype Sets

There is no single set of roles which is accepted universally, but these are the most common and widely known:

- The Eight Hero’s Journey Archetypes

- Michael Hauge’s Four Categories of Primary Character

- Jungian Character Archetypes (coming soon)

The Eight Hero’s Journey Character Archetypes

The hero’s journey archetypes are based on the work of Joseph Campbell, who found that there are some things shared across cultures and time which appeal to our human psyche at the deepest level.

He did not ‘invent’ these archetype but discover them after studying a vast canon of human literature and spoken word stories from over thousands of years.

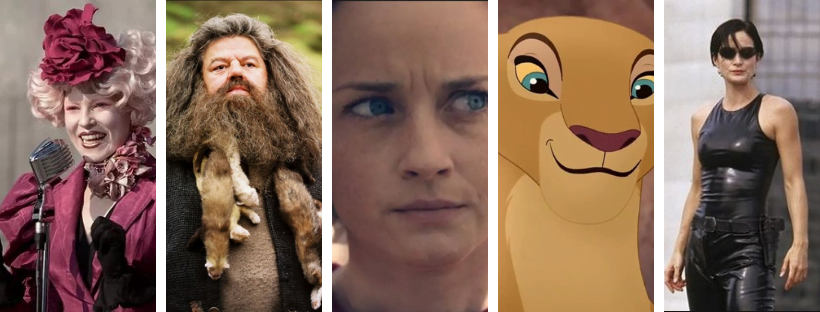

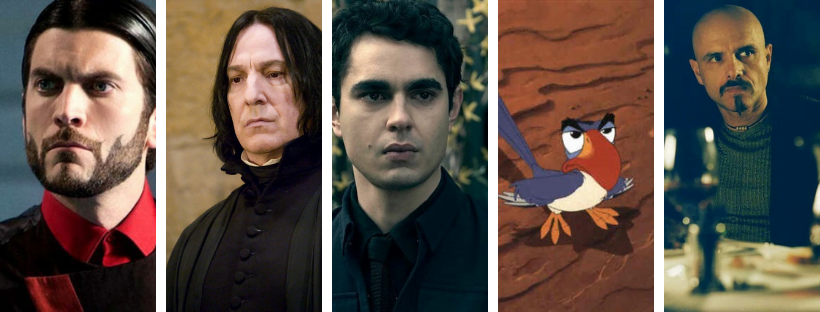

Below we will describe each archetype, and give examples from the following popular books and movies:

- The Hunger Games

- Harry Potter

- The Handmaid’s Tale

- The Lion King

- The Matrix

A few notes about the examples

Bear in mind that characters will fit the archetypes to varying degrees – some will be a perfect fit for the archetype, others may seem to only vaguely resemble the description.

We have added notes to explain why each character represents that archetype.

The interpretation of characters as particular archetypes is so subjective, you may not agree with our analysis – that’s totally okay, there are no definitive right answers.

The intention is to provide writers with a useful tool, not restrictive rules.

Where you find the information useful – use it. Where you don’t – ignore it.

We’d love to hear your comments and suggestions – please comment below.

The Hero

The Hero is the focus of the story, the main character who is followed from beginning to end. They will be the most prominent character, and it’s important they grow and change as a person as the story develops.

We follow them from their everyday life into new and uncharted territories, through a series of conflicts as they attempt to achieve an objective.

The audience should empathise with the Hero and want them to achieve their goal, even if they don’t agree with everything they do.

It’s also important that the hero has agency – they must be active in their journey, not passively allowing things to happen to them.

Examples: Katniss Everdeen, Harry Potter, Offred, Simba, Neo.

Notes on examples –

The hero is usually the easiest archetype to define and the above ones fit neatly into the stereotype of being the most prominent character, whose journey we follow throughout the story and who is different at the end of the story to how they began.

The Mentor

The Mentor is someone who teaches the hero to navigate the new situation they find themselves in.

The Mentor will often be kind and wise, but that’s not a given. Some Mentors might be bad-tempered, drunk or appear superficial.

Their tasks may include: explaining the rules of the new world, giving the hero a confidence boost, helping them access their innate skills and giving them useful equipment.

The Mentor will usually be an important character during the early stages of the story, but will fade away as the plot progresses, so that the hero must face their final battles using their own strength and resources.

Examples: Haymitch and Cinna, Hagrid and Dumbledore, Aunt Lydia, Mufasa, Morpheus.

Notes on examples -

Haymitch is a fairly obvious Mentor as he is outrightly named as the mentor within the book. He provides insider advice on strategy and tactics. However, Cinna also fulfils many of the mentor functions – offering moral support and equipment that assists (the flaming outfit that catches the attention of the audience).

Dumbledore is the obvious Mentor figure in Harry Potter, offering wise council. But Hagrid is the one who first teaches Harry about the new world, is his guide when he firsts enters it, helps him gain access to his funds and helps him gather various equipment (including an owl).

Aunt Lydia may not seem an obvious mentor at all. However, Aunt Lydia explains a lot about the new world the handmaids find themselves in, and while she does not intend to give the hero confidence, it is in defiance of the relentless unjustness of her behaviour that Offred finds strength. By casting such a negative character with many of the tasks of mentor, Atwood underlines the friendless, oppressive nature of the world she creates.

Mufasa and Morpheus are clear mentor characters, providing wise, fatherly figures who are not around for the hero’s final tests.

The Ally

The Ally is a friend of the hero, who gives them assistance as they head towards their goal.

They can also serve as a sounding board and to show contrast with the Hero.

For example, the Hero can explain their plan to the Ally, and so share it with the reader.

And where heroes are instinctive and impulsive, Allies will often be found to be more cautious and thoughtful.

Examples: Peeta and Rue, Ron and Hermione, Nick, Timone and Pumbaa, Trinity

Notes on examples –

In each of these cases, these characters are consistently on the side of the protagonist (even though we have our suspicions about Nick). They discuss the hero’s plans, back them up in battles and also tell them when they’ve acting stupid.

The Herald

The Herald brings the invitation or threat that jolts the hero out of their everyday life and marks the beginning of the adventure.

The Herald isn’t always a person, it is often a letter or some other form of message.

If the Herald is a character, then they may also fulfil one of the other roles – if not, they may have a minor role at the beginning and not appear again.

Examples: Effie Trinkett, Hagrid, Ofglen, Nala, Trinity

Notes on examples –

Although everybody already knows about the Reaping, Effie provides a voice and representation of the authority behind it.

Some might say the letters are the Herald in Harry Potter, but Hagrid is the one who actually delivers the message to Harry that he’s a wizard. He successfully delivers the invitation to Hogwarts and very much jolts Harry out of his everyday life.

Ofglen reveals she is part of the resistance, and opens Offred’s eyes to the possibility of revolt.

While Nala and Trinity also play love interest roles in their respective movies, they are both the messengers that inform the heroes that they need to act (The Lion King is unusual in its structure in that the call to action comes about halfway through the movie, rather than nearer the beginning).

The Trickster

The Trickster is an interesting role that often fills two contrasting purposes.

On the one hand, the Trickster provides comedy and light relief. But at the same time, the Trickster will often draw attention to serious underlying themes. They can make you laugh but also raise important questions.

Examples: Haymitch, Hagrid, Moira, Rafiki, Mouse

Notes on examples –

All these characters stand out as providing amusement, either through their haplessness, wit or playfulness. However, several also represent darker underlying themes: Haymitch shows that even winning the Hunger Games doesn’t lead to a golden future, as he constantly drowns his misery in drink. Hagrid is an early representation of the prejudice against half-bloods, which is a major theme through the series. Moira has the darkest story of all, suffering cruelly at the hands of Gilead for refusing to conform.

The Shapeshifter

Shapeshifters are hard for the hero to pin down. One minute they are a staunch ally, the next they are revealed to be a secret betrayer. But suddenly, when the hero needs it most, the Shapeshifter shifts again, helping the hero out, even to their own detriment.

Having a character like this makes for extra tension and interesting, unpredictable relationships that keep the audience guessing.

Examples: Seneca Crane, Professor Snape, Nick, Zazu, Cypher

Notes on examples –

Each of these characters are difficult to clearly place into the box of either ally or enemy.

Seneca Crane is a clear antagonist throughout most of the story, but ultimately allows both Katniss and Peeta to emerge as victors – and pays for that decision with his life.

Professor Snape is very strongly portrayed as an antagonist, but is fundamentally a committed ally of Harry.

Nick is an extremely difficult to pin down character, and Offred spends the entire novel unsure whether she can trust him, even when he seems to be her closest ally.

Simba certainly sees Zazu as antagonist rather than ally, and while Zazu does want to protect the cub’s best interests, he’s quite happy if that involves thwarting Simba’s own desires.

Cypher is a straightforward betrayer, pretending to be an ally only as far as he needs to, to achieve his own objectives.

The Guardian

The Guardian is a major obstacle on the hero’s adventure.

They stand on a threshold which the hero must cross if they want to move closer to their goal. It may be a real threshold, like a gate or a wall, or it may be something less tangible.

The Guardian wields power, whether it’s physical or bureaucratic, and they are a force to be reckoned with.

Examples: The genetically modified beasts, the Dursley family, The Commander, The Hyenas, Agents Brown and Jones

Notes on examples –

All of these characters are major problems for the hero. In the cases of the genetically modified beasts, the Hyenas and Agents Brown and Jones, these characters are genuinely trying to kill the hero and their allies. They outnumber and outgun them.

Uncle Dursley is not trying to kill Harry, but he does everything in his power to stop Harry accessing his new world of magic. As Harry’s legal guardian he has great power over him, as well as being physically imposing and having the resources of an adult as opposed to a child.

The Commander is the most complex guardian, as he appears to bear no overt animosity towards Offred at all – in fact he appears to quite like her and to want to make her life more bearable. However, underneath the kind exterior, he is actually a major architect of the new world order, and one of the most powerful men in the government. On a whim he could destroy Offred, so she must tread very carefully around him.

The Shadow

The Shadow is the main opponent of the hero.

This character tries to stop the hero achieving their goals, throwing obstacles in their way whenever possible. The obstacles may be physical, mental or emotional – the Shadow will pull no punches.

Examples – President Snow, Voldemort, Serena Joy, Scar, Agent Smith

Notes on examples –

President Snow and Voldemort are both powerful leaders with vast resources at their fingertips (granted, in the first Harry Potter book Voldemort is in a weakened state, but he’s still formidable). Similarly, Agent Smith is the most senior of his type, with seemingly limitless resources and control over the environment.

Although the Commander technically has more power in Gilead, his attitude towards Offred varies from indifferent to something resembling caring. It is Serena Joy who really sees Offred enough to despise her. She holds the power of life and death over Offred, uses violence against her and is also extremely powerful in their world.

Michael Hauge’s Four Categories of Primary Character

Hero

The hero is the main character, and they drive the story. The Hero is on screen or page the most, and the audience should empathise with them.

The audience should want the Hero to achieve their goal, fear for the safety of the hero when they come up against difficulties and rejoice in their success.

The hero must have an internal goal, and some internal conflict.

Nemesis

‘This is the character that stands most in the way of the hero achieving his or her outer motivation.’

The nemesis is most often a villain, but that doesn’t have to be the case. They may be indifferent to the hero, or even feel positively about them – but they must be blocking them achieving their goal.

Nemeses are usually powerful and formidable, as this makes the struggle against them more thrilling.

It’s critical that the nemesis be a specific character, not an idea, group of people or a force of nature. So not ‘poverty’, ‘the CIA’ or a hurricane. These things can certainly be obstacles, but they won’t work effectively as the nemesis as readers will find it difficult to emotionally engage with them.

Note – although the nemesis must be a specific person, that doesn’t mean the reader necessarily knows who it is through the story. They just know there is a person out there creating obstacles.

Reflection

The reflection is usually sympathetic to the hero, and supports them as they strive for their goal.

The reflection provides support to the hero – after all, nobody can do everything alone. They also provide someone for the hero to talk to, sharing information and revealing inner motivation and inner conflict. They also provide a way to show contrast with the hero, to reveal both their strengths and their weaknesses.

Romance

The romance is as you might expect – the romantic interest of the hero.

According to Hague, a character only fulfils this role if winning their affections is a definite part of the hero’s goal.

If the hero is attracted to someone, but is not focussed on achieving their love, then that character is not a Romance in the primary role sense.

At some point in the story the Romance should support the hero’s goal, but at some point in the story they will also oppose it. There will be conflict, and then depending on the story, the Romance may end up supporting the hero in achieving their goal again as the story progresses.