This article is available in video format!

Now we’ll get into the nitty-gritty of writing a plot that is compelling, logical and balanced.

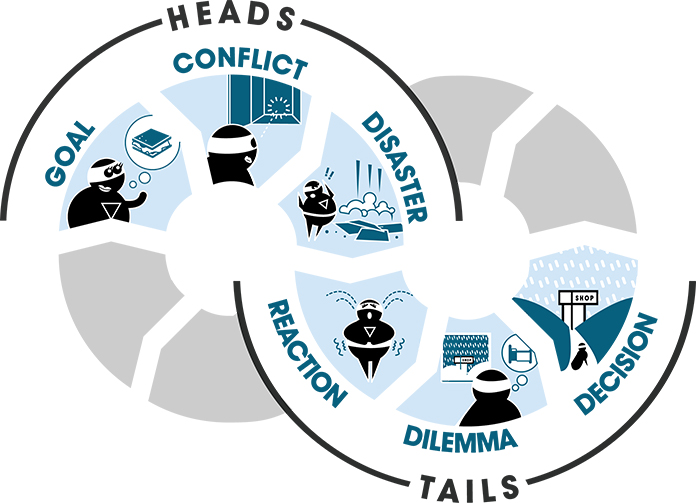

We’ll do it with the cunning use of Head and Tail scenes. This method is based on Dwight Swain's 'scenes' and 'sequels', which you can read more about in his book Techniques of the Selling Writer.

Roughly speaking, Head scenes are where your character is being active, doing stuff, hopefully getting into trouble, getting into people's faces, that sort of thing.

Sounds good right? Action is exciting and keeps the reader glued to the page?

Yes, but if the action is unrelenting, the reader will become fatigued, and the action will begin to feel monotonous.

Which is why we balance the Head scenes with Tail scenes – sections where the characters take some time to stop, reflect and regroup.

By skilfully alternating between these two types of scenes – and energies – it is possible to keep the stakes rising throughout the story, while taking the reader on a rollercoaster of tension, giving them just enough time to almost recover from one conflict before plunging them into the next.

Tail scenes are also useful because they give the opportunity for character development and emotional evolution.

Now, although you should have a roughly equal number of Head scenes and Tail scenes, the word count doesn't need to be split evenly between the two types of scene. The balance decides what sort of story you have.

If 80% of your prose is contained within the Head scenes, you've got a fast-paced, action type story. If it's stacked 80% in favour of Tail scenes, it will be slower paced and a more reflective, thoughtful story.

Both of these types of story are perfectly good. What’s important is that the balance of action to reflection suits the type of story you're aiming to write.

As a general rule, Head scenes should be immediate, happening right here and now, with the action described in detail. Whereas, in Tail scenes it's possible to compress time more, skipping over weeks, months or even years in a few sentences or pages.

Head Scenes Breakdown

Head scenes can be broken down into three parts:

- Goal

- Conflict

- Disaster

At the beginning of a Head scene, your character should have some kind of goal, something they want to achieve. Otherwise it's possible for them to spend the whole scene mooching about, and very few people want to read about that.

So your character should go for their goal and get it, right? Wrong. Boring. Your character should go for their goal and -bam! Conflict!

Something stops them achieving their goal. Now your reader is interested. They want to know if the character is going to overcome this obstacle to achieve their goal. If you're good, you won’t just give them one obstacle, you'll come up with a series of mounting obstacles. Then...

Disaster! Not only does your character not achieve their goal, but they're in a much worse situation than before they started. After all that excitement, they're spent. In fact, the disaster was so great, they may even be locked up. It's time for a Tail scene.

Tail Scenes Breakdown

Tail scenes can also be broken down into three parts:

- Reaction

- Dilemma

- Decision

The first bit is their reaction to the disaster. It should be an emotional, internal reaction rather than an external active one (we'll get to that later). Are they furious? Despairing? They've been through a lot, they ought to feel something.

Once the emotions have had a chance to settle, they're going to start assessing the situation. What are they going to do next? They should have at least two options, though they may have more. At a most basic level, the two options are sit there and do nothing, or take action.

Ideally, there will be no good options. Having good options makes things too easy, and readers don't want to read about someone waltzing through the story easily - they want to see them struggle and strive, so they can root for them, and genuinely worry that they'll be thwarted.

Having weighed up all the options, the character settles on one. The least bad one. Though it's risky, it's worth it, in order to stick to their principles. Now they've got a goal, and the cycle is ready to turn once more.

And repeat

By applying this pattern skilfully to all of your scenes, your story will keep gaining momentum and will feel balanced and real to the reader. You'll avoid having a character that seems to just leap to conclusions out of nowhere, or meandering scenes with no direction.

Applying the Goal to Decision Cycle and coming up with appropriate things for Goal, Conflict etc is usually tricky at first - it takes a bit of trial and error and getting used to – but once you get the hang of it – it will make your novel infinitely stronger than it would be without.

Scenes that aren’t Heads or Tails

Of course, you may really need a scene where your character sets out to do something, and achieves it, or something else which doesn't fit into the structure above. That's fine - you can insert supporting scenes - or Incidents - in where you need them. Just try to avoid having too many of them, or you may find that your story has lost the plot.

Your Task

In the Novel Factory go to the Plot Manager. Make sure that the Related Info sidebar is visible. If it isn't, click to view it using the little tab in the bottom right. In the Related Info sidebar, click on the Goal to Decision Cycle element and complete the fields as appropriate. Repeat for each scene.

Or, you can use the PDF Goal to Decision Cycle worksheet available here.