Novel and Script Editing Tips For Beginners

We are extremely pleased to bring this guest post to you where top editor David Ferris shares his top tips for editing your work. David has 15+ years of editing experience, including with one of the Big Four publishers. Read on to gain insider guidance from a pro.

Whether revising or rewriting, novelists and script writers should follow these practical tips to improve plot, character, humor, and pacing. Punch up your dialogue by streamlining it, spice up each scene with evocative imagery, and make characters more compelling by zeroing in on relationships, not just personalities.

Writing is rewriting

Like “write what you know” and “show, don’t tell,” “writing is rewriting” is one of those old adages (some might say “clichés”) wordsmiths live by. The saying is true: you can’t write good fiction until you’re willing to rewrite, often many times, and that means that completing the first draft is rarely, if ever, the final step. This applies to illustrious, Nobel Prize-winning novelists as much as it does to literary novices.

Think of it this way: writing a novel or screenplay is not like assembling a cabinet, a task that ends with the final turn of the screw. It’s more like putting the whole cabinet together, taking a step back, then taking apart half of it and tinkering with the other half until you’ve reassembled it five different ways. And then repeat.

That’s a daunting task, but don’t let the challenge sway you from the goal. After all, we writers thrive on challenges, right? That’s one of the things we love about the craft, even if it tests the limits of our patience (and our intellect). Use these tips to guide you through your revision process.

1. Read it out loud.

People often say, “Show your draft to a friend or editor—you need a fresh pair of eyes.” But a fresh pair of ears is also valuable. A funny thing happens when you read your text out loud: you engage with and interpret it in a fresh and sometimes startling way. This technique is probably more applicable to screenplays (which are dialogue-based and which are intended to literally be read out loud on screen) but it can be a revelatory experience for novels too. If possible, have someone else do the out-loud reading, or use text-to-speech software. Hearing something in someone else’s voice gives you an insightful perspectival shift.

If the thought of reading out the entire novel is unbearable, then don’t throw away the idea completely – at least read the first few chapters out loud.

2. Cut the beginning and end of scenes, where possible.

In both novels and scripts, most if not all the narrative can be broken down into a series of discrete scenes. Hence, scene work is the essence of all good fiction. Writers tend to front-load scenes with filler or small talk and stuff them at the end with superfluous detail and idle chatter that drag the scene past its emotional climax, thus deflating the tension. You’ll be surprised at how scenes are made livelier, tenser, and more emotionally impactful by snipping away at the beginning and end.

3. Focus more on relationships.

Depending on the state of your draft, this might be less of a “tweak” and more of a major revision, but nonetheless, you should revisit the relationships between your characters and consider what they add to the narrative. In particular, examine how the protagonist relates to others in his orbit (both allies and enemies).

Writers make many mistakes with character (too many to list here), but they also tend to overlook the relationships between characters, which are really what invigorate individual characters and give them depth, definition, and life.

At the scene level, think how you can make characters collide with each other in new, exciting, and perhaps fractious ways (since after all, conflict is the essence of good storytelling).

Tweak the dialogue accentuate the high and low points of character relationships. Think about the chemical reactions between character traits: when you mix various personality types, do they bond, do they stay inert—or do they explode?

4. “Stop and smell the roses” by adding more sensory imagery.

This is more applicable to novelists, who are less constrained by the limitations of cinematic form and screenplay convention, but sensory imagery is important in both mediums.

Unfortunately, authors often get so caught up in working through the plot that they don’t let their characters “stop and smell the roses”—they don’t describe in vivid detail the look, feel, smell, sound, and touch of the worlds their characters inhabit.

A scene could be riveting in every way, but if it’s not vividly evoked in the reader’s mind, it can fall flat, or feel vague and unbelievable. Good description makes for an immersive reading experience—it draws us in.

And by “sensory imagery,” I do mean all five senses: sight is obviously the most compelling, but don’t forget the others. Evocative, precisely worded descriptions of smells and sounds can be especially powerful.

And screenwriters: your page count budget is much tighter and script readers frown on excessive description, but a well phrased depiction of a setting or character can leap like magic from the page and make an inert Courier size 12 line feel, well, cinematic.

5. Take out the said-bookisms.

My favorite literary pet hate (one no doubt shared by editors the world over.) These are dialogue tags (the “he said” and “she said” that attribute lines of speech in fiction) that verge on the florid, excessive, or melodramatic: “he exclaimed,” “she opined,” “he reasoned,” “she insisted.”

For some reasons, first-time writers have gotten it in their heads that said-bookisms are a sign of sophisticated, descriptive writing, but the opposite is true: it’s a tell-tale sign of inexperience. They are distracting, awkward, and undermine the grace and rhythm of your dialogue.

Let the characters’ words speak for themselves. Use fanciful dialogue tags only for moments that warrant emphasis, or to describe a physical action, like “she shouted” when it’s important to specify that she did, in fact, shout.

Utilizing said bookisms is like cooking with white vinegar or curry powder: a little bit goes a long way. Use sparingly; otherwise they’ll spoil your dish.

Dialogue tags aren’t used in scripts, so film and TV writers are fortunately spared the temptation to use them, but the screenwriting equivalent would be too many adverbial parentheticals to describe a character’s speech: (coquettishly); (sheepishly); (psychotically), etc. accompanying a line of dialogue. It infrequently enhances the script and often detracts from it.

Whether and when to use parentheticals in scripts is a subject of fierce debate I won’t wade into now, but the consensus seems to be, as with said-bookisms, rarely, if ever, and only when something would be misinterpreted without it.

6. Add humor, where (in)appropriate.

“Appropriate” in this case offers a lot of leeway. Humor is not just for writers of comic or light-hearted works or subgenres typically associated with comedy. In truth, comedy can be effective in all types of fictional writing, even tragedy or horror, where small moments of comic relief spice up a scene and provide a jarringly pleasing counterpoint.

Even one clever witticism or jolt of irony or perfectly timed joke can make a scene memorable and win the reader’s loyalty. As you review your work, find ways to punch up existing jokes or insert new ones. And jokes don’t just have to be spoken. In both prose and screenwriting, the simple comedy of an uproariously funny image or symbol that stands on its own can leave the audience in stitches. Just don’t force it.

The thing about comedy is that when it’s good, it’s great, and when it’s bad, it’s really bad, and it will kill a whole scene. The reader should never feel that the author is “trying too hard.”

7. Don’t show your hand.

One measure of good writing is that the author doesn’t spell out the subtext overtly. The subtext is the underlying significance of a sentence, scene, piece of dialogue, or event—emphasis on underlying. It’s the 300-pound gorilla in the room. Much of the dramatic force of fiction is derived from that 300-pound gorilla’s presence.

Consider this scenario, one that you’ve probably seen in literature or film in one form or another: a quietly feuding couple, their relationship on the rocks. After days of barely speaking to each other, they agree to a dinner date. He suggests Chinese; she wants Italian. He counteroffers with Indian; she asks him how many times she has to tell him that she hates Indian before he remembers?

What’s the subtext here? It’s obviously not about the choice of cuisine. But it plays so much better because of the ironic gap between what these two characters say and what they mean. The scene would be ruined if one of them came out and declared, “This is so like you—always picking what you want. You don’t even care about my needs!” That is spelling out the subtext, in a way that kills all the delightful tension, drama, and unspoken hostility. Writers do this all the time, to their own detriment.

Fixing subtext problems can be a big job for a novel or screenplay, but often, a few tweaks can go a long way, typically by removing lines rather than adding anything. Scan your draft and see where you are stating the obvious (or not so obvious); then delete it. How does it read now?

Bad dialogue is a frequent culprit, but in novels, calling out the subtext also manifests itself in big internal questions the protagonist poses to herself as she puzzles out the mystery. Why was Sarah being so elusive? Did it mean she had something to hide? Was Jack coercing her to keep quiet? And who put the severed horse head in the bed?

The reason these questions should be cut is that if you have done your job as an author, the reader is already asking himself the same things! And you might think that readers will feel satisfaction at having their speculations confirmed, but the opposite is true: readers (and viewers, if we’re talking about film and TV) like to figure out things for themselves.

When the author states the subtext explicitly, it undermines the pleasure of deduction and interpretation. You wouldn’t want to play poker with someone who turned all their cards face up. I mean, you might—but where would the pleasure be in beating such an incompetent opponent?

8. Revise your opening scene.

The first scene is for obvious reasons among the most important in a screenplay or novel. It sets the tone, introduces (usually) the principle characters, establishes (generally) the narrative, and entices the audience to proceed past page 1. It’s basically a sales pitch, to buyers who have a limitless number of other media they could be watching or reading. If you don’t land the sale right away, you’re in trouble.

Think of the first scene of a script as a movie within a movie. Scenes are in some sense fractals of the whole: they exhibit a similar narrative structure as the film itself. Novels are more structurally free-form and so this analogy might not apply as neatly, but it still helps to think of the first scene of the novel as a book unto itself. Even if you’re just tweaking rather than rewriting entirely, there is always something to improve in the introduction. Give it another polish before finalizing your (manu)script.

9. Save multiple versions.

Forgive me if I’m insulting your intelligence with this banal tip, but the “save as” command is your loyal friend during the entire writing process. Saving multiple versions of your draft is a really simple trick that gives you “insurance” in case you want to undo changes or reference earlier iterations. (It’s also a smart way of backing up the work in case of technical errors, which do happen). I find that by the time I’m finished, I have five to ten saves (not necessarily drafts) of the same manuscript.

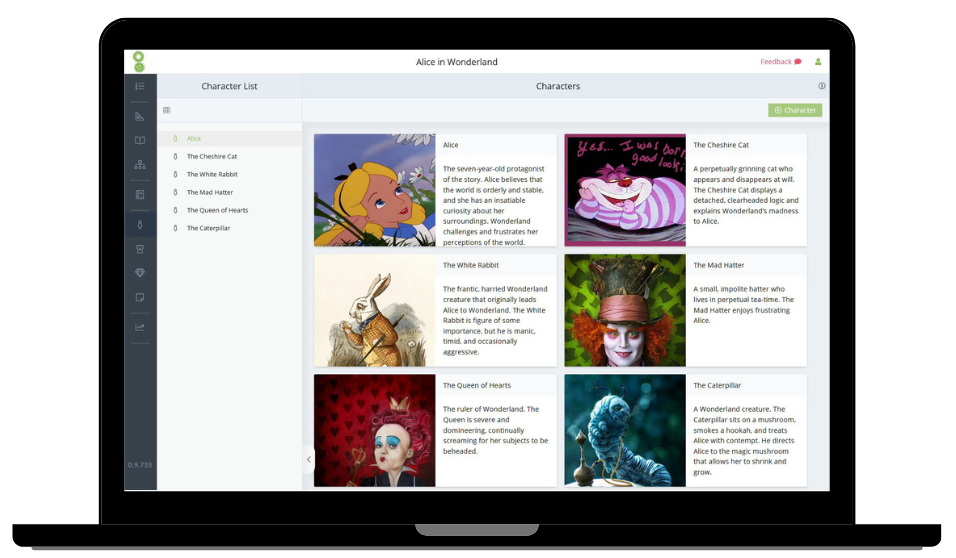

Note from the Novel Factory – The Novel Factory autosaves your work at frequent intervals, so you have regular versions of your drafts saved for referring back to at all times.

I find I rarely go back and consult the old ones, which tells me something about the value of the revision process: rewriting is forward progress, and bits and pieces that you cut from old versions even though you loved them are, like a regrettable ex, quickly forgotten, replaced with something better.

Even so, it’s nice to know I can go back to earlier saves if I need to. In fact, just having them there gives me the freedom to chop and hack and change and alter freely, without fear I’ll make some irrevocable mistake.

And since we’re on the subject: back up everything! No exceptions. Don’t put this off until it’s too late. At all times, maintain three copies of your manuscript: one on your computer, one on an external hard drive, and one in the cloud.

Novel Factory again! Novel Factory 3.0 keeps your work both on your computer and on the cloud. As advised above, it’s also a good idea to export your work regularly to save on an external drive.

DAVID Ferris has enjoyed a distinguished career as an editor, writer, ghostwriter, and filmmaker. His flair for the written word, creative acumen, and meticulous attention to detail has earned him a loyal following of editing and ghostwriting clients, from novice writers to bestselling authors.

Learn more about him and other distinguished editors at Book Editing Associates

Unlock your writing potential

If you liked this article by the Novel Factory, then why not try the Novel Factory app for writers?

It includes:

- Plot Templates

- Character Questionnaires

- Writing Guides

- Drag & Drop Plotting Tools

- World Building resources

- Much, much more