This article is available in video format!

Introduction

“I'm writing a first draft and reminding myself that I'm simply shoveling sand into a box so that later I can build castles.”

― Shannon Hale

It’s time to make some sandcastles.

In this step, we look at redrafting and editing your novel into professional, publishable shape. This is an extensive and detailed article, so get comfortable.

Before we get into the practical details of editing, let’s go through a few general guidelines.

Read it through all the way

Before you start making any changes, read through the entire novel from start to finish.

While you’re doing this, make notes and checklists of things to do (see below), but don’t actually make any changes until you’ve read the whole thing.

You need to have a current sense of the whole novel if your edits are going to be effective.

Find a way to visualise the over-arching story

It’s hard to hold in mind an entire novel, so it helps to find a way to visualise it externally.

Popular ways of doing this can use:

- using index cards

- a whiteboard

- or purpose built software - the Novel Factory provides several ways to get an overview of your novel in the Scenes section.

Whichever your preferred method, you should be able to view the key information from each of the scenes at a glance, and get a general overview of the key storylines.

Make a Plan

It’s a really good idea to make an editing plan. There are several benefits of doing this.

Gives you direction

Having a plan helps you have a clear sense of where you want to be, and how to get there.

Shows your progress

When you’re writing the first draft it’s easy to see your progress as you can simply count the words rapidly increasing. However, with redrafting the words will be going up a lot more slowly, and in fact some of the best progress you make might be cutting words.

Having a plan means you’re able to get a sense of your progress as you can check off tasks as they are completed – and this helps you stay motivated.

Avoids timewasting

If you just dive in without a plan you may find yourself going round in circles, getting diverted or getting stuck down dead ends.

For example, you may find you’re changing something in scene one only to find that it breaks something in scene two, and by the time you’ve fixed that scene five doesn’t make any sense at all, and you realise you need to revert the changes from scenes one and two.

If you make a plan from day one, you can increase your chances that the changes you’re making are not in conflict or going to unravel your plot.

Suggested plan:

Read through the novel and note down anything you want to change, big or small.

Take this list and sort them into:

- Quick wins – e.g. spelling and grammar errors, sentence level improvements

- Mid-level – e.g. tweaking plot points and characters

- Large changes – e.g. new scenes, cutting entire characters

For a quick sense of achievement and to keep you motivated, start by going through all the quick wins. Then, tackle the large changes, because they may affect the mid-level changes and because you don’t want to leave the worst till last. Finally, work your way through the mid-level changes.

Keep old drafts and backups

As you’re redrafting, be sure to keep back-ups and copies of old drafts.

That way, if you realise halfway through a major redraft you’ve made a huge mistake, you can simply revert to the earlier draft. Or if you realise a cracking bit of dialogue or beautiful description that you were forced to cut could actually work somewhere else, you can quickly retrieve it.

(The Novel Factory Online has a Turn Back Time feature, which allows you to view earlier drafts of any scene – even if you didn’t save it).

That’s it for general pointers, now let’s take a look at each of the different levels of editing in detail.

Structural Edit

The structural edit refers to the highest level edit – elements such as character arcs, increasing stakes, and themes.

Progression / Arc

The key question to ask about your story is: How does the main character change between the beginning and end of the story?

Most stories are about change and personal growth, and people want to see that the main character has undergone a transformative journey.

There are exceptions to this, of course. In some stories the main character is already fully formed, but a key supporting character is the one who undergoes the change. Other stories may be more bleak, and may deliberately show a character that doesn’t change in order to represent the futility of existence.

But in most cases, readers will enjoy the evolution of the character. So check if your character changes.

Examples:

In Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Harry Potter starts off a lonely, bullied child who longs for a place to belong. By the end he is a confident young boy with friends who love him, and a school he can call home.

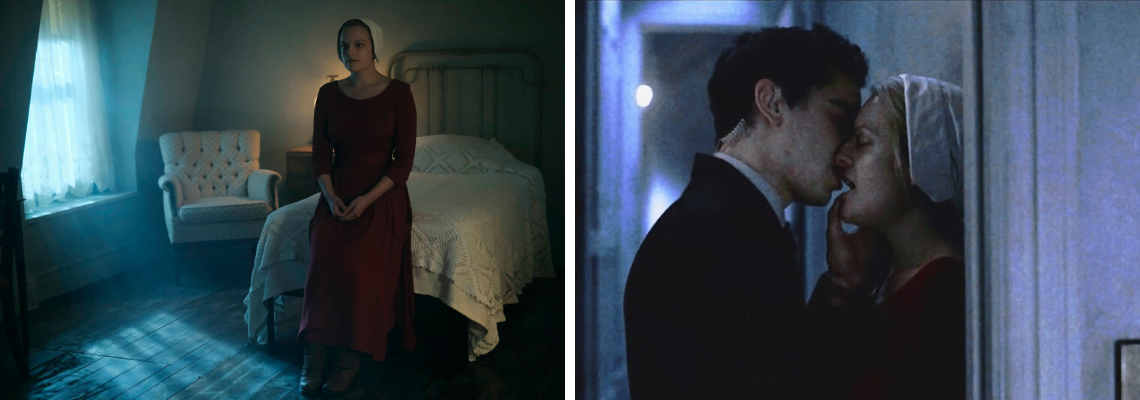

In the Handmaid’s Tale, Offred begins a passive, obedient woman whose body is used for sex but not pleasure. By the end of the novel she is breaking all the rules and risking her life to have an affair because she so desperately needs to feel love and pleasure.

In the Hunger Games, Katniss evolves from being a nobody in the poorest district, to being an icon who challenges the highest authority – and wins.

In the Lion King, Simba changes from being a carefree cub who thinks power is all about doing what you want, to a responsible King who will give whatever it takes to protect his pride and homeland.

See the Character Driven Hero’s Journey for more info on creating an epic character arc.

Increasing stakes

If you want people to keep turning pages, you need to keep upping the stakes and increasing the tension.

It’s not going to work if your protagonist is fighting for their life in scene one, then dealing with a difficult shop assistant in the final chapter.

You could define stakes as:

Goal (what they want) x Conflict (the opposition) x Risk (what they could lose)

Let’s look at each of these elements in more detail.

Goal - In many stories the main character’s goal in the beginning of the story is simply to make it through everyday challenges. By the end they are attempting to saving a loved one, a community, or even the world.

Conflict - Early conflict often comes from a low-level antagonist who is more of a niggling bully, whereas at the end the hero is facing an incredibly powerful individual with real power to cause serious destruction.

Risk - What's at stake often starts out as fairly low importance, relatively easy to get over. But by the end the hero risks losing their loved ones and their own life if they fail.

Examples

In Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Harry starts off just wanting to survive his awful family until school and avoid embarrassment or punishment. By the end he is trying to protect Hogwarts from destruction by the world’s most powerful wizard, and his own life is at risk.

In the Handmaid’s Tale, Offred just wants to get through each day and her biggest worry is being beaten up or kicked out by Serena Joy. By the end she is so desperate to experience human kindness and love that she is willing to risk torture and murder by the all-powerful Gilead government.

In the Hunger Games, Katniss just wants to get through the reaping without being picked, and her greatest opponent is the poverty that leave her and her family hungry. By the end, her goal is to escape with her life, and without being forced to commit murder while the Gamemakers, who control every aspect of her surroundings, do their best to break her.

In the Lion King, Simba the cub just wants to have fun. His biggest opponent is a snooty little hornbill, and the worst thing that can happen is to be chastised by his father. By the end, he is willing to risk his life to save the pride lands from Scar and his army of hyenas.

Themes

As you've been writing your draft you've probably been instinctively following themes appropriate to your story. Themes can be specific or very abstract - a mother's love, the colour blue, loss, autumn, reflections or flying, for example.

Whatever your themes may be, you can lift your novel from good to great with skilful application of themes.

As you read through your draft, see if there are any recurring motifs or messages that seem to be cropping up. Once you’ve identified your key themes, you can tweak them to make them more powerful.

For example, imagine you found that during your first draft you mentioned flying birds several times. You can now take this concept and consider how it can be used to subtly reflect on the story. Perhaps adding a flightless bird in a particular scene could be a significant symbol? Perhaps the lack of birds in a given scene could also be useful as a gesture? In an uplifting scene, perhaps a flock of birds could fill the sky, or in a tragic scene a bird could be shot down?

How subtle or overt you are with your themes is up to you and your taste.

Scene edits

For Scene level edits, we’ll look at the Action Reaction cycle, and Hooks.

Action Reaction Cycle

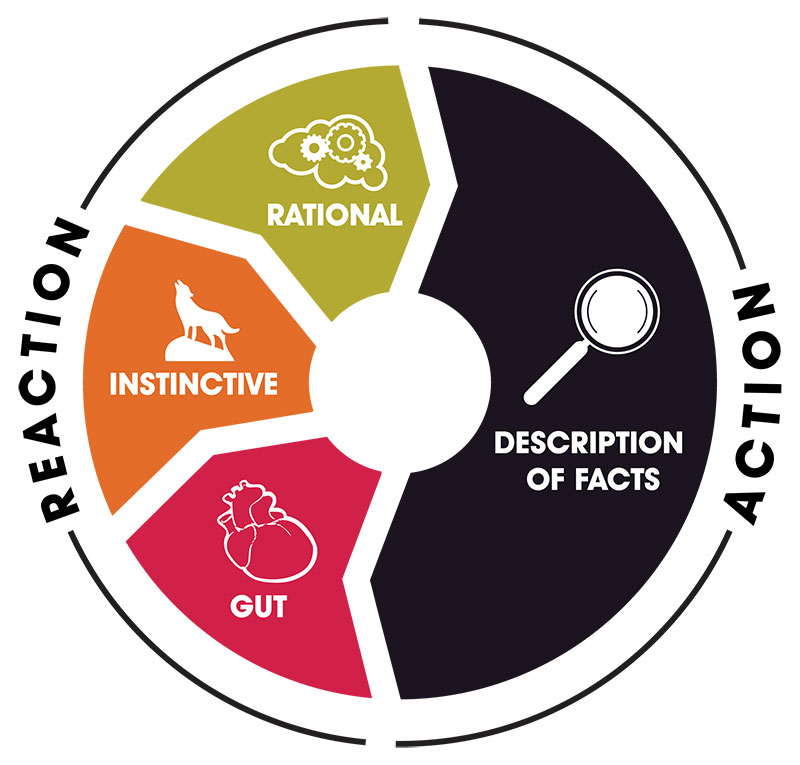

First, the action reaction cycle.

If something about your scene doesn’t feel quite right and you can’t put your finger on why, understanding some action > reaction mechanics can help get to the bottom of it.

This is the action > reaction cycle:

Action

In the action reaction cycle, you start with a paragraph that has an outward description of the action. This should be completely detached from the character’s point of view or opinion on the matter. FACT only. No bias based on the protagonist. This is easier said than done.

E.g. There was a knock at the door.

Reaction

Reaction describes the character’s reaction to the Action and can be split into three parts: Gut, Instinctive, Rational.

Let's look at those in more detail.

Gut - this is a visceral, bodily emotional response. Something like a cold chill down the spine, a tightening of the throat or a twisting in the gut. It doesn't involve any overt movement or controlled thought.

Instinctive - This is still controlled by the body rather than the mind, but it will be more deliberate. It might be leaping back, or reaching for a gun. It may be a helpful reaction, or it may make the situation worse.

Rational - Finally, now we've got through all the gut, instinctive stuff (which probably only took seconds, or less), we can get to the controlled part of things, where the character gets to express themselves. They may have a thought: "Oh no. Not again.", or they may carry out a controlled, deliberate action: "She raised the gun, aimed, and fired." Or both.

Find a section where something doesn’t feel right, and see if applying the principles of the action reaction cycle make any difference.

When you write, cycle your paragraphs between Action and Reaction. The Reaction paragraph does not have to include every part (gut, instinctive, rational) every time, in fact, it would get a bit weird if it did. But it should include at least one, and they should stay in the correct order.

An Example

We'll start with an example where it's done wrong, with all the elements mixed up and in the wrong order:

Lorelei hugged her legs, remained fixed in place, control stolen from her body. So this was it. She was going to end up just like all the others, she thought as she watched the figure at the other end of the beach walking towards her, slowly closing the distance. She felt gripped with a mixture of fear and desolation.

You may think that reads okay, or you may not. But either way, let's compare it to what happens if we rewrite it to follow the Action >> Reaction Cycle:

There was a figure at the other end of the beach, walking towards her.

Fear gripped Lorelei. It stole control of her body, so all she could do was remain fixed in place, still hugging her legs. She watched helplessly as the figure closed the distance between them. So this was it. She was going to end up just like the others.

In this example the first paragraph is only a single line, but it is an, external, indisputable fact. There's a figure, at the other end of the beach, walking towards her.

Next we have the Reaction, first the gut (fear gripping her), then the instinct (all she could do was remain fixed in place, watching helplessly, etc), and finally her rational thoughts about the matter (deciding she's about to meet her doom).

Hopefully you'll agree that the second version is much stronger, and plunges into the story so it feels more real, much more so than the first one.

So as you’re redrafting, whenever you find areas that don’t seem to be flowing, see if giving them the action > reaction cycle treatment helps.

Hooks

Hooks are a key part of grabbing a reader and keeping them exactly where you want them.

Hooks usually come in the form of questions that are raised in the reader’s mind. They may be stated overtly in the text, but more often they’ll be implied.

A masterful storyteller will raise multiple questions through the story, answering some along the way while leaving others hanging. As some questions are answered, new ones will be raised. If this is done skilfully, readers will remain hooked, without feeling like they’re just being strung along.

For example, in Nevermoor: The Trials Morrigan Crow, the prologue starts with a public announcement that Morrigan Crow has sadly passed away. The family are grieving and would like to be left in peace.

This raises the obvious question in the reader’s mind – how is there going to be a whole novel about a character who is dead? This question is answered within the first few chapters, by which time other questions / hooks have been raised.

Style edits

Next we’ll look at style edits, such as show don’t tell, proportionality, and dialogue mechanics.

Show don’t Tell

Show Don’t Tell refers to the advice that rather than explaining your character’s feelings, you should aim to make the reader feel those emotions directly.

For example, rather than saying:

Ben was furious.

You would describe his sensations, feelings and actions:

Ben’s throat felt like it was being crushed by a vice. He clenched his fists by his side and ground his jaw.

Or, in another example, rather than telling the reader what a party was like:

It was a very fancy party, and everyone was really enjoying themselves.

You could describe what guests can see, hear, taste and smell, with tantalising details.

You could barely move for ladies in their finest sequined gowns giggling into their martinis, and tuxedoed gentlemen slapping each other’s backs as they roared with laughter. Conversation flowed as freely as the golden champagne, and everyone agreed that the ice sculpture of Cleopatra was quite magnificent.

By following this rule, you’re more likely to draw your readers into an immersive, genuinely felt experience.

Proportionality

Proportionality is about going into the correct amount of detail. Not rushing things, but not labouring the point either.

A rule of thumb to help with this is to match the level of detail to the importance or emotional intensity of the scene.

So if you’re writing a key scene which is pumped with emotion, then go into the minutae of everything that happens in every moment. Zoom right in.

But if you’re writing a less highly charged scene, then it’s fine to compress the writing: summarise and move through time faster.

Dialogue mechanics

Next, dialogue mechanics.

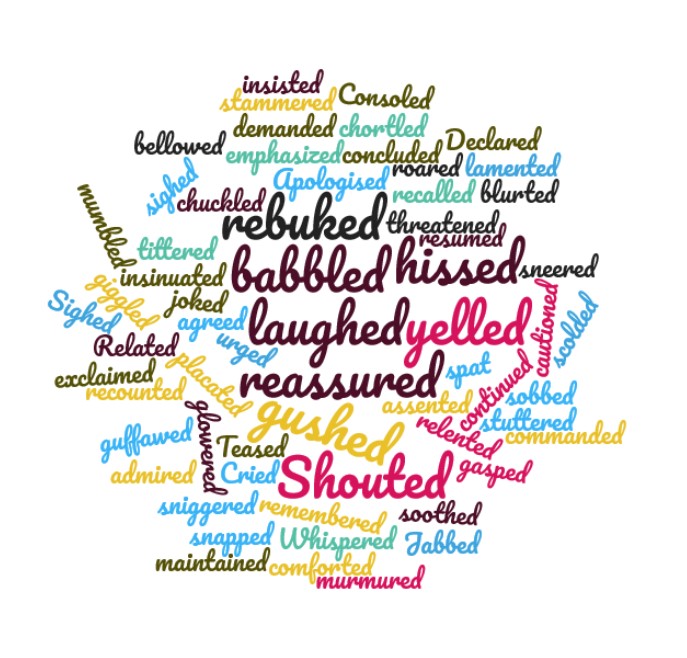

A habit that often sets newer writers apart from more experienced ones is an urge to use different words instead of ‘said’.

New writers can feel that ‘said’ becomes boring and repetitive, and they want to make the writing more interesting.

The problem is that alternative ‘dialogue tags’ such as: exclaimed, interjected or shouted can come across as ‘explaining’ what’s going on to your readers, which falls into a similar category as telling instead of showing.

And if these words are required, it may be ain indicator that the dialogue itself isn’t working hard enough, as effective dialogue will get across the emotional thrust without requiring an explanatory dialogue tag.

Also, the magical thing about the word ‘said’ is that it tends to become invisible as we’re reading. So in contrast to a reader feeling like they’re being bombarded with the same word in a monotonous fashion, they will simply not notice it at all, which allows the dialogue to speak for itself.

A better option for supplementing the dialogue is to use beats of action to emphasise the character’s words. These are physical gestures or external description of the surroundings.

Furthermore, in skilfully written dialogue, it will be clear who is talking from the words they use and the way they say them, so dialogue tags – including said – can often be dispensed with.

Here’s an example to demonstrate the above points:

Read through the following dialogue, which includes lots of descriptive dialogue tags.

Give it back!” screamed Oyinkan.

“No,” replied Abena, petulantly.

“I’ll tell mum,” Oyinkan threatened.

“You wouldn’t dare,” retorted Abena. “Or I’ll tell her what you did.”

Now read the same dialogue, but with the descriptive dialogue tags removed, and some action beats added in.

“Give it back!” Oyinkan’s statuesque frame filled the doorway.

“No,” said Abena, not looking up from her laptop.

“I’ll tell mum!”

“You wouldn’t dare,” said Abena, finally lifting her head to fix Oyinkan with a cold stare. “Or I’ll tell her what you did.”

Hopefully you’ll be able to see how the dialogue is positively affected by these choices.

Line edits

Line edits are where we get into the sentence and word level detail to really polish your writing and make it shine. Here is a quickfire list of eight things to look out for:

Clunky sentences – keep an eye out for sentences that are too long, have too many clauses, or contain ambiguous pronouns.

Clichés – clichés are by definition overused phrases, that are no longer original. They will weaken your writing, so find a better way to say it.

Repetition – weed out repeated words, phrases, sentence styles, and even actions and descriptions.

Word choice – examine each word for atmosphere, accuracy, emotional impact.

Adverbs – adverbs are often an indicator of a weak verb. They don’t have to be avoided altogether, but be skilful and meticulous in your use of them.

Continuity errors – make sure characters don’t change names, locations don’t move around, everything isn’t bone dry immediately after a storm.

Factual errors – for example, these could include anachronisms, the wrong flora or fauna in a location, medical or police procedural inaccuracies - the list is endless.

Spelling and grammar – this is really proofreading rather than line editing, but however you categorize it, you need to make sure you know the basics of accurate language. If you’re not confident with your apostrophes and semi-colons, there’s no need to be ashamed or worried. There are plenty of resources that can help get you up to speed, and spelling and grammar is one of the easiest things to learn about writing a novel.

Your Task

In the Novel Factory, in the Manuscript section, open each scene and redraft each one, using the guidance above. You can also use the Plot Manager, Subplot Manager, Notes, and other sections to keep track of your story.

Or, if you're not using the software, use your preferred writing method.