Show, Don’t Tell: Understand It Once and For All

“Don’t tell me the moon is shining. Show me the glint of light on broken glass.”

Anton Chekhov

If you’ve been writing for any amount of time, you’ve probably come across the phrase ‘show don’t tell’.

Like many pieces of writing advice, it’s extremely useful – up to a point.

However – also like many pieces of writing advice – it’s often misunderstood, and sometimes unfairly used to beat writers over the head with.

If you’re frustrated, because writing tutors keep giving you the feedback to stop showing and start telling, but you’re not really sure how to actually do that, then we’re here to help.

In this article we’ll cover the following topics:

- What is showing and what is telling?

- Why should you avoid telling?

- Showing not telling when describing characters

- Showing not telling when describing settings

- Showing not telling when describing action

- General tips on how to show instead of telling

- Times when it’s appropriate to tell instead of show

Showing vs. Telling: What’s the Difference?

In short, telling is explaining to someone what happened, whereas showing is making them feel like they experienced it for themselves.

Telling tends to feel distant and detached, whereas with showing, the reader is completely immersed in the story, world and drama.

This is best demonstrated with examples.

Telling could be:

- John was very cross. He went to the shed to sulk.

It’s simple, and to the point. There’s no embellishment, detail or opinion. It conveys information about what’s happening, but it doesn’t make you feel anything. And if you read a book that went on like this for too long you may well die of boredom.

So instead, we could do something like this:

- John stormed out of the house, kicking out at the azalea that brushed him as he passed. He stomped down the path and into the shed, slamming the door so hard the whole structure rattled and several tiles clattered down from the roof and shattered on the paving stones. Moments later heavy metal music blared from the cracked window, the wall of sound a clear message: leave me alone.

In the second example, at no point do we explicitly state that John is cross, but there are few people who wouldn’t be able to infer his feelings from the actions described. And in this version you feel much more immersed in John’s experience, more like you witnessed it for yourself.

Why is showing not telling so important?

In writing, we’re always told brevity is desirable, and you should be clear and concise, and not waffle on with flowery language.

Telling is clearly much more succinct than showing, so why is it considered such bad form?

It comes down to the reason most people read books.

They don’t come to be told a story.

They come to live someone else’s life. To vicariously experience feelings and emotions that aren’t available in their every day.

People read romances to feel lust and desire. They read thrillers to feel excitement and fear. They read suspense to feel tension. And so on, for all the genres.

People want to be transported to another world, and be immersed in someone else’s drama.

Showing is how you immerse them.

When you effectively ‘show’ with your words, the readers aren’t just watching the main character feel pain, lust or fear. They actually feel those sensations and emotions for themselves.

Studies have shown that witnessing someone else’s actions or pain ‘can trigger parts of the same neural networks responsible for executing those actions and experiencing those feelings firsthand’ (source).

But being told ‘that person is in pain’ is not enough to trigger this effect – we have to see it for ourselves, even if that is an image conjured in our mind’s eye from words on a page.

How to show not tell in your writing

Showing versus telling when describing characters

People don’t come wearing a badge that says ‘I am truthful but forgetful’ or ‘I am a well-read perfectionist’, nor do they openly declare such things on meeting you.

No, we get to know people’s personalities, backgrounds and interests from a range of different clues, such as how they dress, how they move, how they talk, what they say, how they treat others and what they do.

So, if you want your readers to feel like your characters are real people, rather than cardboard cut-outs, you need to let those readers get to know the characters for themselves, without you making unsubstantiated claims.

In other words, you need to show, not tell.

For example, telling might be:

- Samantha is vain and deceitful.

Whereas you could show the same information like this:

- Samantha glanced at the mirror that always leaned against her computer, and tutted, tucking a stray wisp of hair behind her ear. Two hours at her dressing table this morning, already her damn hair was misbehaving. Perhaps she should try out that new serum after all, even though one bottle would cost her half a month’s wages. Her perfectly manicured nails drummed on the table. Only she knew that in the drawer underneath was the designer lipstick she had swiped from Marjorie’s handbag while she was in the loo. Marjorie really should know better than to leave something like that lying around in the open. Her mouth twitched at the memory of poor Marj accusing Phillipa of the theft and she chuckled. It wasn’t like she’d told Marjorie it had been Phillipa. She’d just dropped a few subtle hints and then sat back and watched as Marj thought she was so clever, putting two and two together.

In the second passage we use detail and action to allow the reader to witness Samantha’s character and draw their own conclusions.

Here’s a masterful example of a passage that shows us the colour of someone’s character, without ever explicitly stating it. In the following passage, the speaker is talking about his wife, while his wife is in the room:

“Madame,” said Azaire, “I assure you that Isabelle has no fever. She is a woman of a nervous temperament. She suffers from headaches and various minor maladies. It signifies nothing. Believe me, I know her very well and I have learned how to live with her little ways.” He gave a glance of complicity toward Bérard who chuckled. “You yourself are fortunate in having a robust constitution.”

Birdsong, Sebastian Faulks

Although this quote is of Rene Azaire describing his wife, it tells us far more about Azaire than Isabelle. Through this passage, we get the clear impression that Azaire is misogynistic, patronising and dismissive of his wife. His word choices and sentence structures also give us clues about his social class, education level and background.

Showing versus telling when describing settings

Showing not telling is critical when describing settings, if you want your reader to feel like they’re really present in a real place, rather than observing a static photograph.

There are three key ways to achieve this:

- Provide access to all of the senses

- Relate the environment to the physicality of the point of view character

- Relate the environment to the emotions of the point of view character

Again, let’s show this through examples:

- It was a sandy beach, and the hot sun beat down. At the end was a beach bar with lots of people drinking cocktails.

In the telling example, we just state what can be seen, though the sensation of heat is mentioned, albeit in a passive way.

If we really want the reader to have the sensation of being there, we might do something like the following.

- I felt the warm sand squeezing between my toes, the grains satisfyingly tickly. The heat of the sun was like a physical pressure, and beads of sweat oozed from my shoulders and ran in warm trickles down my back. From up ahead, past the gently nodding palm trees, wafted the sound of chinking, oversized glasses and tipsy laughter. A fruity aroma drifted towards me with sharp tang of alcohol, and the colourful umbrellas and pineapple cubes bursting from the glasses were too much temptation for me to resist.

In the second version we don’t use the words ‘beach’, ‘bar’, or ‘cocktails’, but you can probably see all those things much more vividly than in the first version, and may even have had echoes of the sensations described.

All of the senses are addressed:

- Sound – the sounds of chinking glasses and laughter

- Sight – gently nodding palm trees, colourful umbrellas

- Smell – fruity aroma, tang of alcohol

- Touch – sand between toes, heat of sun, trickle of sweat

- Taste – the taste of pineapple and fruity cocktails is alluded to, thought not directly experienced.

And these senses are directly linked to the physicality of the point of view character. We also touch on their emotions, with ‘satisfaction’ and ‘temptation’.

It’s important to note that while these are useful ways to nudge your writing more towards showing rather than telling, this example is deliberately extreme. It’s not often you will cover every single sense in a single paragraph and you won’t generally stay quite as close to the physicality as this for pages on end.

Here’s an example from the ‘real world’:

“I wake to the sounds of streaming water splattering into a porcelain bowl. The scent of lavender mixed with rose drifts through my bedcurtains. My eyes flutter. The curtains are drawn slightly.”

The Belles, Dhonielle Clayton

Clayton doesn’t spend a lot of time describing the size and shape of the room, or the exact furniture, but through evocatively describing specific sounds, smells and sensations, we feel like we are right there with the main character.

Showing not telling when describing emotions

This is probably when it’s most important to show rather than tell.

Because as mentioned above, most people read to feel. So if you’re not letting them experience the emotions directly, you’re not delivering on what they picked up your book for.

The original John example at the beginning of the article covered anger, so this time, let’s use the example of lust.

A telling of lust might be:

- He was so sexy, I was uncontrollably drawn to him, and I couldn’t think straight.

This doesn’t seem so bad, does it? But what if we try to apply the principles of showing, not telling? Perhaps we’d end up with something like this:

- My heart pounds in my throat and my armpits prickle. When I speak all that emerges is gibberish. When he is not there I can form full sentences. When he is there… It’s like nonsense verse. The way his t-shirt hugs the muscles of his arms, the way his eyes crinkle when he grins…

The physical details and extra specifics bring the passage to life, taking it from monotone to full colour.

Finally, here’s an example of someone conveying nerves, without saying it outright:

His throat went dry. His palms moistened. Unable to reach for his handkerchief in the packed downtown subway, he wiped both palms on his pants.

Behold the Dreamers, Imbolo Mbue

What are some tips for showing, not telling?

Use all the senses

An excellent way to make the story more immersive is to appeal to as many of the reader’s senses as you can. Humans tend to be a sight driven species, and a lot of writing necessarily describes what can be seen.

By weaving in descriptions of what the point of view character can smell, feel, hear and taste, you bring the situation to life in three dimensions.

Use strong verbs instead of adverbs

Adverbs tend to feel like telling, as you’re explaining how something is happening, whereas if you use a strong verb, the reader sees for themselves. Furthermore, a strong verb will often convey a lot more meaning than a weak verb together with an adverb.

For example:

- Gibson walked slowly to school.

Versus:

- Gibson strolled to school.

- Gibson meandered to school.

- Gibson shuffled to school.

All these three examples express that he’s walking slowly, but they express more about how Gibson is feeling.

Use dialogue

Using dialogue is a great way to make a scene leap into life.

While it is possible to ‘tell’ in dialogue, if you use a character as a mouthpiece for an awkward info-dump, dialogue itself is always immediate and active.

Dialogue is also an excellent way to get a character’s personality across directly to the reader.

For example, without me saying anything about the age, gender, class or background of the speakers, how much can you infer from the following quotes?

“Alright mate, how’s it going? You going down the pub tonight? Ready to get another thrashing at pool? I could do with a bit of extra beer money.”

“Hello, dah-ling! How wonderful it is to see you! Tell me, could I tempt you into a cheeky snifter at the club this evening? I do believe they’re putting together a bridge competition, and the grand prize is lunch with the Prime Minister!”

Use specific details

Don’t just say the storm raged.

Describe how it pulls up trees by their roots, how the windows rattle like they’re about to burst free from their frames, and watch as a car is slowly lifted and turned over.

Link everything to character action

Instead of saying there was a lamp on the table, have the character turn it on.

Instead of saying she had long brown hair, have her flick her ponytail, or toss her hair over her shoulder (or ideally something less cliche, but you get the picture).

Instead of saying she was cross, have her stamp her foot.

Every time you link something to a character’s action, you are making it come alive and showing the reader the action for themselves.

Self study

The best way to learn how to be effective at showing not telling is to study the difference for yourself. Look at the examples above, and see if you can identify what makes telling different to showing different – and what makes them effective, or not.

Can you write your own ‘showing’ passages to replace the ‘telling’ ones?

Next time you’re reading fiction, see if you can spot examples of great showing. How does the author do it? Can you practice doing the same for yourself?

Read through some of your own work and try to identify if you’re showing or telling. Can you make the story more immersive by switching some of the telling for showing?

Is it ever okay to tell?

Yes. There are times when it is okay, and appropriate to tell.

In fact, despite how often ‘show don’t tell’ is repeated like some kind of authorial mantra, almost all writing is a mix of showing and telling.

This is because if you used showing for every single piece of information you needed to get across, then you’d never get the story started.

Sometimes it’s okay to simply describe a room or garden without needing to invoke every sense, You can just say there’s a lamp on the table (though ideally you’ll describe the lamp in a specific way that gets across something about the person who’s lamp it is). If a character had to interact with every bit of furniture in a room just so the reader knew it was there, then they’d constantly be bouncing around like some kind of over-caffeinated octopus.

One particular time telling is necessary, is when you’re compressing time. If you need to skip over hours, days, weeks or even years, then you might want to bridge that gap with a few explanatory sentences. Starting to investigate senses and emotions in that situation would feel odd.

For example, if describing a character’s morning, it would be fine to say:

I got up, threw on some clothes, and hurried out the door.

Rather than feeling you have to describe the feel of putting clothes on, the smell and taste of the food, and how the character feels about all those things, if it’s not relevant to the plot or characterisation.

So, how do you know if it’s okay to tell?

Like with most aspects of writing, there are no hard and fast rules, and ultimately you have to make the decision about what’s best for you and your readers, but here are a few rules of thumb to try to help:

- If it’s not an important part of the plot.

- It is not of dramatic interest

- If you need to skip over some time

Summary

Hopefully you now feel confident in identifying what is showing and what is telling.

And you understand not only why showing is so desirable, but also how to do it.

Don’t forget to keep an eye out for showing or telling in books that you’re reading, and try to spend time analysing your favourite examples.

And remember – there is a time and a place for telling – just make sure you know when you’re doing it and why.

Here are a few links for further reading:

https://www.enchantingmarketing.com/show-dont-tell-storytelling/

https://jerichowriters.com/show-dont-tell/

https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/ShowDontTell

Note – almost all articles on Show Don’t Tell reference the quote at the beginning of this article, but turns out, it’s not what Chekhov actually said. Find out the truth here.

If you liked this article, then you might want to check out our Novel Writing Roadmap.

Unlock your writing potential

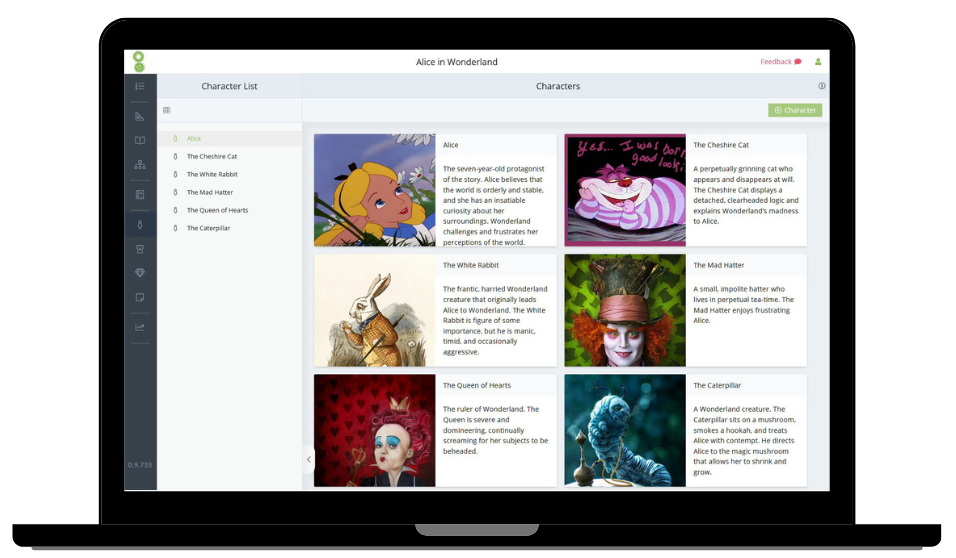

If you liked this article by the Novel Factory, then why not try the Novel Factory app for writers?

It includes:

- Plot Templates

- Character Questionnaires

- Writing Guides

- Drag & Drop Plotting Tools

- World Building resources

- Much, much more