The Origins of Western and Eastern Storytelling — and Why They are Different

Guest post by Neil Wright

Where you are and where you have grown up plays a massive part in how you perceive the world. It is our cultures that shape who we are.

Most people tend to think of culture as the superficial surface phenomena of clothing and certain sporting events and festivities. They don’t realise just how deeply it shapes our understanding of the world.

Culture distorts how we experience life, the way we think about it, and the way we behave.

Consider some of the most remote cultures on Earth to see how big the differences can be.

In the West, cannibalism is one of the greatest taboos. Yet, in Papua New Guinea, eating the Dead is an intimate funeral passage for loved ones. Westerners routinely eat billions of kilograms of beef. Yet in India, cows are sacred.

With these massive differences taken into account, it shouldn’t surprise anyone to learn that our models of the world are influenced by the environment around us. And the environment around us, in turn, influences the way we tell stories.

The Purpose of Storytelling

All human societies that we know of — from the rich industrial West to the smallest hunter-gathering tribes — tell stories.

The evolutionary purpose of storytelling appears to be as a vessel for transmitting lessons and cultural norms to others, with the goal of helping people work out how they can control or restore order in certain situations or to a particular environment.

In most cases, stories are told by adults who transmit ideas to children of what is and isn’t fair in life, what they should and shouldn’t value, and how they should behave if they want to fit in with the values of society.

As a result, stories often come pre-packaged with moral lessons, punishments and rewards — and are shaped in ways that reflect the culture in which they are told.

This is thought to be a very powerful and important technique that is drilled into children as their brains are still in a state of plasticity and developing. It is especially important in children aged 7 years or younger.

Western Stories

Western society has a culture of individualism.

Children in the West grow up viewing themselves as individuals. It is believed that the perception of self in the world of individualism began with the ancient Greeks.

People in the west also tend to view life through a prism of a series of choices and personal liberties. They view the world as though it is made up of many different parts and fragments.

Some psychologists believe individualism is a product of the geography of Greece’s rocky and hilly environment — meaning ancient Greece wasn’t suitable for large-scale agricultural projects.

So, in order to succeed in Ancient Greece, people tended to work on their own or in small businesses, as fishermen or the producers of olive oil, for example. Their geography inevitably fostered a culture of individualism.

For the ancient Greeks, then, self-reliance bred success. Individualism and the mastering of one’s own destiny became crucial in order to master the environment that the ancient Greeks found themselves in.

While this isn’t a perfect theory, it is certainly a fascinating one. It could explain how it was the ancient Greeks who invented the individual.

With this in mind, it perhaps isn’t surprising the Greeks began to glorify the all-powerful individual along with personal glory, progress and the art of perfection. Remember, it was the Greeks who invented the Olympics — the ultimate competition of self versus the self.

The Greeks also told mythological tales about Narcissus and the danger of self-love. And of course, the Greeks also practiced an early form of individual voting rights and the Democratic process.

If there was a theme to ancient Greek culture and literature it was that, with enough self-determination, the individual could master their own destiny and choose the life that they wanted.

We see this arc — essentially the progenitor of the Hero’s Journey — countless times in Greek mythology and storytelling.

Eastern Stories

It couldn’t be more different in the Far East. For starters China, the mother culture for both Korea and Japan, is literally on the other side of the planet, separated from the Greeks by thousands of miles, mountains and deserts.

The Greeks would have almost certainly have been aware of China — but nevertheless would have remained a larger mysterious, remote place.

China’s landscape also couldn’t be more fundamentally different. In China, wide-open spaces are abundant. The land is fertile and ripe for agriculture.

In such an environment, it was reckoned that in order to survive, people needed to be the complete opposite of the individual.

Success hinged on reliable team players working in large group endeavours in agrarian fields — such as rice or wheat irrigation projects or in the harvesting of other crops.

In China, group effort was paramount, which also meant fitting in and getting on with your peers, rather than operating in small businesses.

This theory is understood by psychologists as the ‘collective theory of control’. In such a situation, in China and the Far East, the collective idea of the self was born.

China’s most famous philosopher, Confucius, makes frequent reference to collective ideals in his writings.

For example, he talked about the idea of what it takes to be a ‘superior man’ and how the superior man is one who ‘does not boast of himself’ because he instead ‘prefers the concealment of virtue’.

Confucius notably stated that this concealment would lead to equilibrium and harmony. Compare Confucius’ writings to an ancient Greek philosopher and the answers could hardly be more different.

So, for Easterners, mastering one’s environment meant cooperating through a group effort. That is how the Chinese came to look at reality and success.

In eastern philosophy, existence is understood as a field of interconnected forces, not individual fragments as perceived by the Greeks.

However you look at it, it would be naive to think that these fundamentally different outlooks of philosophy would not impact the storytelling that arises from these host cultures.

Beginnings. Middles. Endings?

Most Western storytellers are aware of the three-act structure. Aristotle labeled these acts the beginning, middle, and end. We can also refer to them as the phases of crisis, struggle and resolution.

In Greek myths, there is usually a singular protagonist who overcomes enormous odds and obstacles after leaving his homeland, defeats the antagonist and returns home a hero (often with treasure).

This is a classic example of how Greek myths embodied ancient Greek ideals of the individual, and how the individual can master the environment.

They are stories of how any person, so long as they have courage and determination, can accomplish anything if they put their mind to the task.

Such morals and stories influence Westerners from a very young age. Scholarly studies have revealed that when asking children to make up a story they tend to follow this three act Greek model subconsciously.

In China of course, things are different.

Autobiographies are popular in the West but in China there were virtually none of them until the modern-day. And of the few that do come out, they tend to have the personal tone of voice removed. They read like the insights of an onlooker reflecting on a life, rather than the perspective of the person telling their life story.

Western stories are straightforward cause-and-effect, largely.

But Eastern stories tend to have a large cast of characters that all reflect on the plot’s drama. And in almost all cases this cast of characters will have conflicting and contradictory takes on the drama.

The effect, then, of Eastern stories like this, is to try and put the reader in a position where they have to figure out what happened on their own.

A classic example of this is ‘In A Bamboo Grove’ by Ryunosuke Akutagawa. This murder story is told from the POV of several different witnesses — and a spirit of the victim itself.

In Eastern storytelling, it is uncommon for there to be a clear unambiguous ending or a sense of real closure. You will be hard pressed to find a happily ever after in a story from the Far East. Instead, the reader has to disentangle the ending for themselves.

This is how Easterners tend to get pleasure out of their stories.

The Unifying Power of Story in Culture

There aren’t many eastern origin stories where the drama hinges on individuals. But that doesn’t mean they don’t exist. However, when an individualistic story does come about, the heroic deeds tend to be achieved not by the individual but by cooperation and in a group-like manner.

In the West, heroism defeats evil, the truth is set free and love prevails. But in Eastern literature, true heroism is attained through sacrifice. Especially if that sacrifice protects the family and the wider community.

In Japan, there is a model of storytelling known as ‘kishotenketsu’ that is structured around four parts and isn’t unlike the Greek myths.

For example, we are introduced to the characters in part one, the drama begins in part two, and there is something akin to a midpoint in part three. But in part four, things get very different.

The reader is usually encouraged, in an open-ended way, to try and look for a sense of unity and harmony between all the story’s parts.

It might frustrate some Western readers to follow an Eastern origin story with an ambiguous ending. But to an Easterner, it makes perfect sense. After all, life is complicated and without clear answers.

Eastern readers take pleasure from the narrative discovery of harmony, whereas in the West, readers enjoy accounts of individuals struggling against the odds and winning the day. The differences lie in how both cultures perceive change.

Westerners see the world as essentially a jigsaw to be put back together when drama arises in the story. For Easterners, life is a never-ending field of interwoven forces. The desire for readers in the Far East is to attempt to restore these forces so that they fit harmoniously, so they can all peacefully co-exist.

While the stories may be different in structure and ending, universally the purpose of storytelling is the same. Both Easterners and Westerners — and everybody in between — tell stories as lessons in control.

Stories play important cultural roles such as helping people to orientate themselves, and find their way and place in the environment around them. They are ways of managing the reality we find ourselves in, attempts to reign in the chaos.

—

About the Author

Neil Wright is a copywriter for a transcription company based in the UK called McGowan Transcriptions. His main hobbies include reading and writing. He is currently working on his first novel.

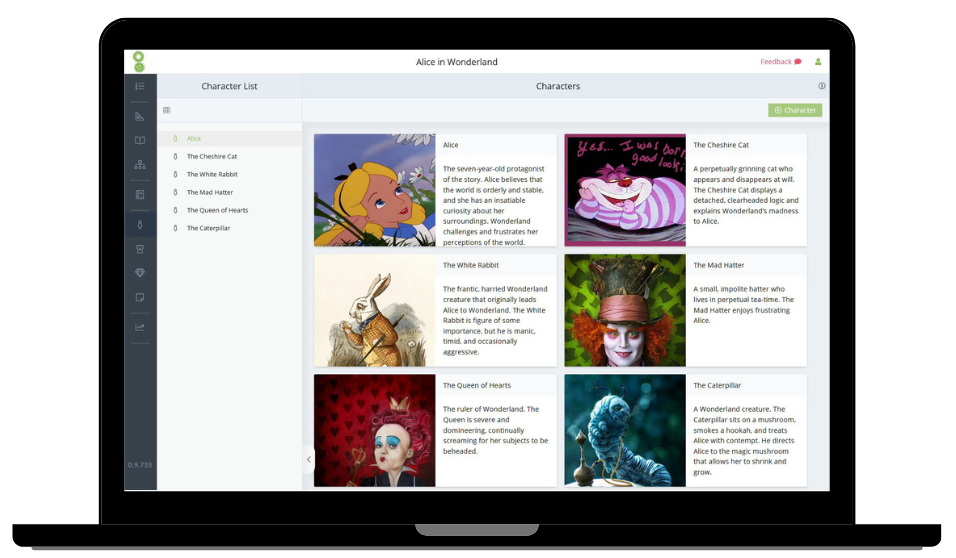

Unlock your writing potential

If you liked this article by the Novel Factory, then why not try the Novel Factory app for writers?

It includes:

- Plot Templates

- Character Questionnaires

- Writing Guides

- Drag & Drop Plotting Tools

- World Building resources

- Much, much more