Parts of a Story: A Beginners Guide to the Five Basic Elements of a Story

There are certain elements every good story needs.

If you skip any one of them, there’s a good chance your story will fall flat and fail to resonate with readers. They’ll struggle to lose themselves in the world you’ve created and have little concern for what happens to your characters.

No one ever sets out to write a bad story. But that’s the risk if you don’t have all the foundational pieces in place.

The good news? You can avoid writing a weak story by building a strong foundation. Learn the parts of a story, how they all fit together, and why they matter, and you’ll become a better storyteller.

Are you ready?

The 5 Basic Parts of a Story

Let’s look at the five main parts of a story in detail.

1. An Unforgettable Main Character

Characters are what stories are made of. They help us explore the human condition, even if they’re not human. (malfunctioning robots, anyone?)

And the most important character in all stories is the main character.

Chances are, an idea for your main character will have come to you as a core part of your story idea, or very soon after.

You probably know their gender, rough age, nationality and maybe a little about their personality.

For some writers, that’s enough, and the rest of the character’s personality and backstory will emerge as they write the novel.

A lot of writers, however, prefer to flesh out their main character as they are developing their plot, because the two things are so interdependent.

To help ensure your main character is someone your readers are going to want to spend a lot of time with, you need to build empathy with them (even for characters who aren’t very nice). This can be done by showing them to be kind, skilled, competent or liked by others.

Or if your character really is a nasty piece of work, then make sure you make them funny. We are liable to forgive a host of shortcomings if someone is still able to make us laugh.

Further to that, you may want to consider the following aspects of your main character:

- Positive traits

- Negative traits

- Motivations (see Objective, below, for more on this)

- Flaws

- Quirks and mannerisms

- Fears and Phobias

- Most treasured possession

You don’t have to define every single aspect of your main character right at the beginning, but try to make sure they feel rounded and interesting, to get you off to a good start.

2. An Extraordinary Situation

Of course, your characters can’t walk around in a void.

In some types of stories, the setting will be a critical part of the story, almost a character in itself, such as a talking space station or a slave ship lost at sea.

But even those where the setting is more everyday, it still needs to play an important role, creating its own specific conflicts, pressures and tensions for your characters.

But why does the title say ‘situation’ rather than ‘setting’?

Setting usually refers to the time and place, such as Victorian England or Futuristic Mars.

But ‘situation’ emphasises that there is more to the setting than that.

There were many stratas of society in Victorian England. Is this story set around the poverty stricken areas or the decadent ones?

And there might be specific things about this setting in this book, such as Vampires roaming the streets, or a threat or war from abroad, or a new invention that is about to change everything.

When talking about futuristic Mars, the situation could involve a threat from an alien species, or lack of resources.

Or the situation could be related to internal politics. Or if the story is a romance, the setting / situation could involve a culture where partners are assigned at birth based on DNA, but the main character falls in love with someone else.

So explore your setting beyond geographic location and year, and see how it can be used to enhance your story, and its themes and conflicts.

3. A Compelling Objective

Everyone wants something.

And the more your character is willing to do, to get what they want, the more compelling your story is likely to be.

In the real world, people don’t always have clear objectives. They may change their minds frequently, or they may not be very serious or motivated about attaining their goals. While that’s the norm, it’s also not very exciting — so it doesn’t make for good storytelling.

So in fiction, it pays for your characters to have clearly defined wants and needs.

Your first step is to consider what your character wants from their normal life. Do they want to be rich? Catch a criminal? Find their soulmate? Save the planet or their own livelihood from ruin?

But what the character wants often turns out to be different from what they actually need. What the character needs is the heart of the story, and what makes the situations much juicer.

For example, maybe your leading man is striving for money and power (his want) because he never felt he had the approval of his domineering father (his need). But once he gains wealth and position, he finds he’s still unsatisfied, as his need is still not met. Only if he’s insightful enough, or has outside help, will he realize he’s been chasing the wrong outcomes, and with self-acceptance he can finally feel at peace.

Wants (external goals) tend to relate to money, power, possessions and possessive love. Whereas Needs (internal goals) tend to relate to courage, compassion, belonging and self-acceptance.

So consider what your main character wants, and what they really need.

4. A Challenging Opponent

Every good novel needs conflict. It’s the driving force behind a good story. It builds tension, excitement, and interest. As a matter of fact, without conflict, there is no story.

While there will be multiple conflicts of different levels throughout your novel, when it comes to the core story parts, we’re thinking about the key opponent—the nemesis.

While the opponent can be a force of nature, an organisation, or a situation, the most powerful ones to hit our human psyches are usually personified.

Voldemort is an obvious ‘Bad Guy’, who is a power-mad, intelligent lunatic.

In the Matrix, the whole world seems to be against them, but we are given a face to focus our fear and courage against, in Agent Smith.

In the Hunger Games, the opponent is the whole system, and the Gamemakers, but the general is made specific in President Snow.

Good opponents aren’t just random evil-doers, their goals directly conflict with the main character’s, and they often act as a reflection, showing what could happen to the main character if they take the wrong path, or fail to find courage or integrity.

It’s important that opponents are powerful formidable opponents. They have to seem impossible to beat, and they must have serious power or control over the main character’s chances at happiness.

5. Impending Disaster and Realistic Stakes

If you’ve hooked your reader with the gripping situation, made them care about your main character and what they desire, and had them rooting for the character against a worthy opponent, then you only have one thing left to do.

Thrill them with an exciting and satisfying ending.

Even successful discovery writers (those who write the novel without planning the plot in advance) usually say that they know roughly how their story is going to end when they start writing.

Your novel will have much better direction if you know where it’s going. And you’re going to want to end with a bang.

So the final key story element is a ‘disaster’.

This may be an actual disaster that occurs, which the main character has to face as their final challenge. Or it may be a looming catastrophe that the main character needs to avert or avoid.

While life or death situations are naturally high stakes and are therefore popular in fiction, it’s possible to grip readers with much more day to day goals and disasters, if you set it up well.

The possibility of losing $20 or $100 in a card game isn’t interesting enough to hold anyone’s attention for long.

But potentially losing the Poker World Championship, after playing for decades and overcoming incredible personal challenges along the way, including the defeat of a shady, evil, and vengeful opponent, is much more riveting.

So think about the finale of your story, and how your main character will be tested. Once you know that, you’ll be able to ensure that they spend the rest of the story gaining the skills they need in order to triumph.

These are the five basic building blocks of your story. But they’re only your starting point.

Other Story Elements to Consider

Once you’ve got the basics, you’ll start adding these additional story elements.

1. An Intriguing Theme or Central Question

Theme is interpreted in different ways, but we use it to refer to the story’s central moral question.

Your theme is the question you want to ask and answer through your story.

Maybe that question is “Do good guys always finish last?” or “Does crime ever pay?”

Theme usually involves moral explorations of a universal idea, message, or lesson that underpins your entire novel.

Your novel is your thesis, where you try to prove the truth of your theme.

Why does theme matter? Because people have a basic need to understand the human condition, and story is one of the main ways we accomplish this.

From a writer’s perspective, a central moral question helps focus your story and gives it deeper meaning. It’s what makes your book emotionally rewarding to readers.

Your theme doesn’t need to be obvious. Instead, use it as an internal guide. Keep it in the back of your mind as you write your story, rather than trying to crow bar it into every scene.

2. A Distinctive Voice

Voice is one of the hardest parts of being an author to pin down, but it might help to split it into three separate categories: The Main Character’s Voice, the Book’s Voice and the Author’s Voice.

The Main Character’s voice will get across the personality of the character. Are they serious or silly? Do they like the sound of their own voice or prefer to think everything through carefully? What sort of vocabulary do they use? What’s their sense of humour?

All of this will come across not only in the words they use in their dialogue (though that is key) but also how they describe the people and situations around them.

The Book’s voice will go beyond the main character. Some books have a whimsical, chatty style of narration. Others, the narrator is almost invisible. Some books go deeply into sensual descriptions using advanced vocabulary, others are sparse and give you only the broadest brush strokes.

The Author’s voice may vary from book to book. Authors will use different tones and styles if writing in different genres or for varying age groups. But Author’s voice is probably the one you need to worry about the least, because it will emerge naturally from your personality, experiences and influences.

The best way to learn about Voice is to see how other authors handle it. In some books the Voice will be so strong it will be unignorable. In others it might be more subtle. Think about which books appeal to you the most and study what techniques the author uses to create a unique and engaging Voice.

You could even try writing something in the style of one of your favourite authors.

3. Effective Symbolism

Symbolism is one tool authors use to convey information without spelling it out explicitly. For example, you might dress a villain in black or a hero in white, use an overcast day to imply sadness or heartbreak, or have birds swooping through the skies to represent freedom.

Good symbolism bypasses the conscious and hits us straight in the subconscious, making us feel a certain way without us being aware of what’s happened.

Like using the weather, clothing and surroundings to convey ideas and emotions, skilled writers will use similes, metaphors and vocabulary choices.

A writer wishing to convey a mood of quiet, simmering threat might describe a train station where darkness oozed, with a gloomy, deserted waiting room, blackened brick walls, a queue snaking across the hall, and the bellow of steam trains like angry beasts tethered to their task with bellies of hungry flames that hissed and crackled.

Alternatively, a writer wishing to create a lighter mood might describe the platform as being filled with bustling families, giggling children in bright colours, the gentle breeze making the sunflowers sway and bob.

The gleaming train would proudly slide into the station and sigh in satisfaction as the conductor blew his brass whistle and fluffy clouds drifted lazily by, overhead.

4. Engaging Subplots

Subplots can make or break your story.

Strong ones add depth and can help you to explore different aspects of your central question.

Subplots move the story along in the same way your main plot does, but often involve secondary characters and/or secondary conflicts.

While you won’t spend as much time developing your subplots, they can be nearly as important as your main plot—some would argue truly effective subplots exist because they must. Without them, you simply couldn’t tell your story.

For example, in the Hunger Games, the main plot involves Katniss’ fight for survival. But the subplot of her romance with Peeta, while adding backstory, insight, and a ‘will-they-won’t-they’ suspense throughout the book, plays an integral role in the end.

So be sure to examine your own subplots. Are they adding to your novel? Are they essential to it? How can you strengthen them?

Master Story Elements and Write a Better Novel

If you’re just beginning your author journey, there’s no better place to start than learning the essential parts of a story.

Now that you’ve got the basics, can you see ways to make your own novel stronger?

Have you got all five elements? Do any of them need to be developed in more depth?

Decide what you need, then check out our writer’s resources for help.

Or, why not visit our Facebook community to ask questions about the Parts of Story, and share yours with us!

Unlock your writing potential

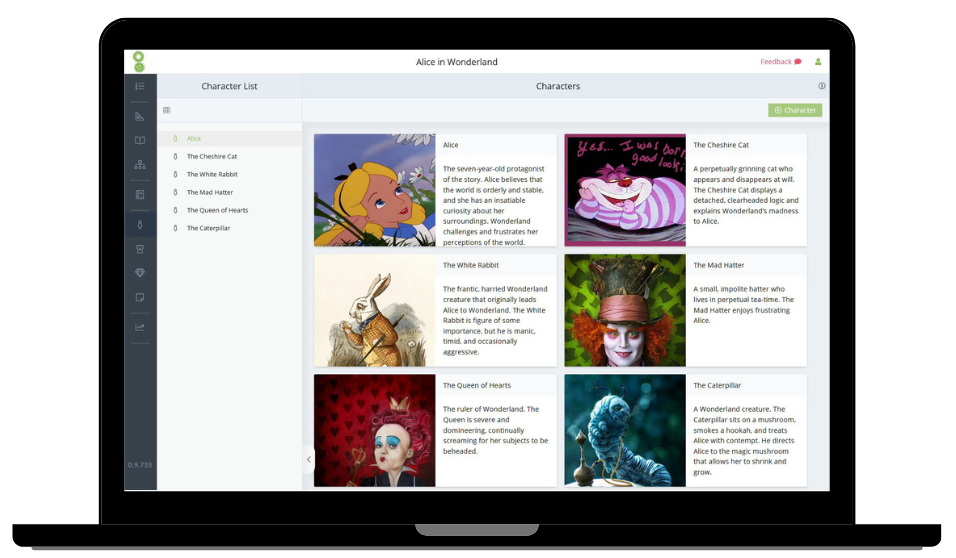

If you liked this article by the Novel Factory, then why not try the Novel Factory app for writers?

It includes:

- Plot Templates

- Character Questionnaires

- Writing Guides

- Drag & Drop Plotting Tools

- World Building resources

- Much, much more